| HOME | BACKGROUND | CASES | REFERENCES | PRESS | CONTACT US |

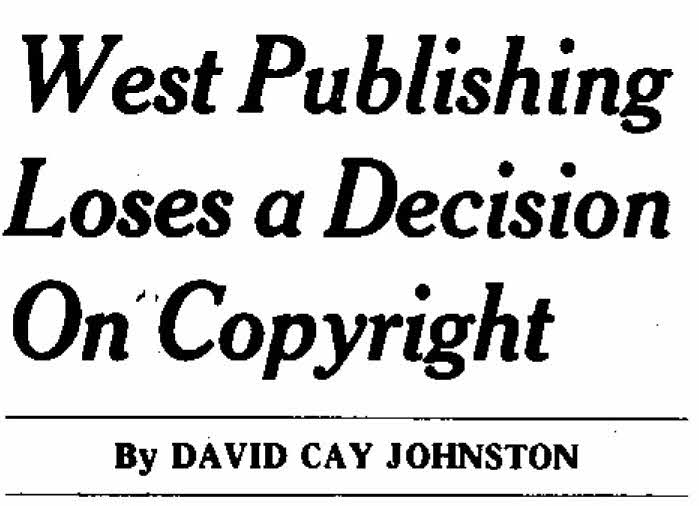

This is just one of nine different decisions through which West Publishing Company lost its copyright claims on both the TEXT and the CITATIONS to its National Reporter System. WEST and LEXIS were parties to secret agreements which HyperLaw discovered and then used the antitrust proceedings to obtain. "HyperLaw makes reference to at least four documents that it thinks the Government should have disclosed as determinative in formulating the proposed consent decree: 1) a 1988 agreement between West and Mead Data Central (then-owner of Lexis-Nexis) settling a copyright dispute over the use by Lexis of star pagination to West's National Reporter System; 2) a 1996 agreement between Thomson and Lexis-Nexis extending licenses for the use of Thomson legal and non-legal content by Lexis-Nexis; 3) a 1997 agreement between Thomson and Lexis-Nexis for the divestiture of certain products to Lexis-Nexis; and 4) the "mutual antitrust release" between Thomson and Lexis-Nexis that was attached to and made part of the divestiture products sales agreement. According to HyperLaw, these documents -- especially the 1988 agreement -- "are mentioned prominently in the papers filed in the court below by the Appellees and by Amicus Curiae Lexis, and were also mentioned in out-of-court statements made a part of the record," all of which demonstrates that the Government considered these documents in formulating its proposed consent decree." --D.C. Circuit

On the appeal, West was represented by famous Harvard Law School Professor Arthur R. Miller.

The Second Circuit held: "The arrangement of cases in the West case reporters, however meticulous and thoughtful, is of small assistance to the primary use of these products--searching for cases, and retrieval. After all, the useful order of access is almost always determined by the research goal of each user rather than the publisher's sequencing (a compilation of law cases being not much like a musical medley or a sonnet sequence). And the primary use of West's pagination in plaintiffs' products is to allow the user to refer to the location of a particular text within the West case reporters as has become standard practice in the legal community. West concedes that use of its volume and page numbers for pinpoint citation purposes is at least a fair use (if it even amounts to actionable copying). There is no evidence that plaintiffs have encouraged the users of their products to reproduce West's arrangement. In fact, the CD-ROM products provide no easy means for using the star pagination to create a substantially similar arrangement; a user must retrieve each case, one at a time, in the order in which they appear in the West volume, [**32] and then print each one. What customer would want to perform this thankless toil? "

|

|

LEAD TRIAL AND APPELLATE COUNSEL

United States Court Of Appeals For The District Of Columbia Circuit HyperLaw, Inc., Appellant v. United States of America, et al., Appellees

No. 97-5183 1998 U.S. App. LEXIS 12921 May 29, 1998, Filed COUNSEL: For HYPERLAW, INC., Amicus Curiae - Appellant: Carl J. Hartmann, III, Law Firm of Carl J. Hartmann, New York, NY. For HYPERLAW, INC., Amicus Curiae - Appellant: Paul Jonathan Ruskin, Law Offices of Paul J. Ruskin, Douglaston, NY. For HYPERLAW, INC., Amicus Curiae - Appellant: Lorence L. Kessler, Law Office of Lorence L. Kessler, Washington, DC. For UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff - Appellee: Joel I. Klein, Assistant Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice, (DOJ) Antitrust Division, Washington, DC. For UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff - Appellee: John P. Fonte, Attorney, Robert B. Nicholson, Attorney, U.S. Department of Justice, (DOJ) Antitrust Division, Appellate, Washington, DC. For THOMSON CORPORATION, WEST PUBLISHING COMPANY, Defendants - Appellees: Wayne Dale Collins, Shearman & Sterling, New York, NY.

GINSBURG, SENTELLE, and RANDOLPH, Circuit Judges. JUDGMENT This appeal was considered on the record from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia and on the briefs and arguments of counsel. The court is satisfied that appropriate disposition of this case does not call for a published opinion. See D.C. Cir. Rule 36(b). For the reasons in the attached memorandum, it is ORDERED and ADJUDGED that the orders and judgment from which this appeal has been taken be AFFIRMED. The Clerk is directed to withhold the issuance of the mandate herein until seven days after disposition of any timely petition for rehearing. See D.C. Cir. Rule 41. MEMORANDUM The Antitrust Procedures and Penalties Act, a.k.a. the Tunney Act, provides that when the Government proposes a consent decree in an antitrust enforcement action, it must make available to the public [*2] copies of the proposed decree together with "any other materials and documents which the United States considered determinative in formulating such proposal." 15 U.S.C. § 16(b). In this case HyperLaw challenges a series of orders by the district court that culminated in a consent judgment approving the acquisition by the Thomson Corporation of West Publishing Company. We understand HyperLaw's briefs to raise two issues: (1) whether the district court erred in finding that there were no determinative documents within the meaning of the Tunney Act, and (2) whether the district court erred in determining that no further public notice and comment was needed before it ruled that the proposed consent decree was in the public interest. A. Standard of Review HyperLaw argues for de novo review because this appeal involves "errors of law by the district court in applying a federal statute and findings of fact that are predicated on a misunderstanding of the governing rule of law." The Government notes that this court has left unresolved whether the district court's underlying findings in a Tunney Act case are reviewed under the "clearly erroneous" standard or are reviewed de novo. [*3] See United States v. Western Elec. Co., 301 U.S. App. D.C. 268, 993 F.2d 1572, 1578 (D.C. Cir. 1993). The Government suggests that we review for clear error the district court's finding that there were no determinative documents and that we review for abuse of discretion the district court's decision not to order further notice and comment. For purposes of this appeal we may assume without deciding that HyperLaw is correct to insist upon de novo review, for we must uphold the decisions of the district court even under that non-deferential standard. B. Determinative Documents HyperLaw makes reference to at least four documents that it thinks the Government should have disclosed as determinative in formulating the proposed consent decree: 1) a 1988 agreement between West and Mead Data Central (then-owner of Lexis-Nexis) settling a copyright dispute over the use by Lexis of star pagination to West's National Reporter System; 2) a 1996 agreement between Thomson and Lexis-Nexis extending licenses for the use of Thomson legal and non-legal content by Lexis-Nexis; 3) a 1997 agreement between Thomson and Lexis-Nexis for the divestiture of certain products to Lexis-Nexis; [*4] and 4) the "mutual antitrust release" between Thomson and Lexis-Nexis that was attached to and made part of the divestiture products sales agreement. According to HyperLaw, these documents -- especially the 1988 agreement -- "are mentioned prominently in the papers filed in the court below by the Appellees and by Amicus Curiae Lexis, and were also mentioned in out-of-court statements made a part of the record," all of which demonstrates that the Government considered these documents in formulating its proposed consent decree. The main thrust of HyperLaw's argument is that the purpose of the Tunney Act is to prevent courts from "rubber-stamping" proposed antitrust consent decrees; in HyperLaw's eyes, the district court's acceptance of the Government's statement that there were no determinative documents is just the kind of rubber stamping that the Act was designed to halt. HyperLaw maintains that these agreements must be disclosed in order for the court and the public to "make any real sense out of the proposed Consent Decree." In its brief the Government relies upon our decision in Massachusetts School of Law v. United States, 326 U.S. App. D.C. 175, 118 F.3d 776, 784 [*5] (D.C. Cir. 1997), for the proposition that the term "determinative documents" encompasses only documents "that individually had a significant impact on the government's formulation of relief -- i.e., on its decision to propose or accept a particular settlement." Actually, the quoted proposition was the Government's litigating position in MSL, not the court's holding, which was that "the Tunney Act does not require that the government give access to evidentiary documents gathered in the course of an investigation culminating in settlement." 118 F.3d at 785. Although our holding in MSL was not as broad as the Government claims, it does follow from MSL that a document is not determinative merely because the Government considered it in the course of its investigation. Here, HyperLaw's submission shows only that the Government had access to the documents in question and that it considered them in formulating the proposed consent decrees. The evidence consists principally of newspaper reports about the merger and letters from Thompson and Lexis-Nexis mentioning various aspects of the licensing agreements. In its brief HyperLaw asserted that the Government had referred to "central, [*6] critical, and finally determinative documents in virtually every pleading filed" (emphasis in original), but when pressed at oral argument HyperLaw's counsel could identify but a single sentence in the Government's competitive impact statement saying that "only two licenses to use West pagination have been issued by West." Without more, that sentence is plainly insufficient to support the inference that the Government considered the 1988 agreement to be determinative in formulating its proposed consent decree. To sum up, even if, as HyperLaw believes, "the government relied on these documents in its investigation and in framing the proposed relief," it does not follow that the documents were determinative within the meaning of the Tunney Act. HyperLaw has given no reason for us to doubt the Government's assertion that there were no determinative documents in this case, much less any reason to pick out as determinative the few documents it seeks. C. Notice and Comment The Government published its proposed consent decree for public notice and comment in July 1996 and revised the decree in response to the comments it received. HyperLaw argued before the district court that [*7] the notice was defective because the licensing agreement for star pagination was never disclosed. Upon appeal HyperLaw has shifted its focus somewhat; now it emphasizes that the decision to sell all of the divestiture products to Lexis-Nexis changed the terms of the deal in a way that required additional public comment. We agree with the Government that the court should treat notice and comment under the Tunney Act as "analogous to agency rulemaking notice and comment." The purpose of the notice and comment provisions in the Tunney Act is to enable the district court to make a determination whether the proposed consent decree is in the public interest. As long as the final consent decree is a "logical outgrowth" of the proposed consent decree, there is no need for successive rounds of notice and comment on each revision. Further notice and comment should be required only if it "would provide the first opportunity for interested parties to offer comments that could persuade the agency to modify its [proposal]." American Water Works Ass'n v. EPA, 309 U.S. App. D.C. 235, 40 F.3d 1266, 1274 (D.C. Cir. 1994). Here, the original public notice of the proposed consent decree was adequate. [*8] As discussed above, the Government had no obligation to disclose the 1988 licensing agreement between West and Mead Data Central as a determinative document. The Government made only minor modifications to the proposed decree in response to comments, so the final decree was a logical outgrowth of the proposed decree. Although HyperLaw is correct that the public never had an opportunity to comment on the decision to sell all of the divestiture products to Lexis-Nexis, that decision did not alter the terms of the proposed decree, which (as the Government observes) neither "required nor prohibited the sale of the divestiture products to any particular entity." The district court sensibly regarded the potential anticompetitive effect of the sale to a single buyer as an issue separate from the alleged anticompetitive effects addressed in the consent decree before it. D. Conclusion HyperLaw has evidence that the Government knew about the four putatively determinative documents it seeks, but that is not enough to make those documents "determinative" within the meaning of the Tunney Act. On the question of notice and comment, HyperLaw can identify nothing in the final decree that was [*9] not a logical outgrowth of the proposed decree that was published for public comment. Therefore, the district court did not err, whatever the standard of review, and the orders and judgment under review are Affirmed.

|

.jpg)