| HOME | BACKGROUND | CASES | REFERENCES | PRESS | CONTACT US |

THE COURT: Why are we going into this, Mr. Hartmann? I know that he lied. You can't say it much more clearly than that. MR. HARTMANN: That was the point. This was the official who was on the ground with regard to all of these things. THE COURT: The depart-ment itself has admitted it. MR. HARTMANN: They aren't the witness though, your Honor, so I just wanted to proffer that. THE COURT: I am certainly going to accept the depart-ment's representations that this gentleman lied under oath.

--Trial Tr. v. 2, p. 209, l. 13

"THE COURT: The government's position is what? And do you admit, by the way, or have you admitted that there is no basis for those statements of Mr. Sewell's? MS. WELLS: Yes, I believe in interrogatory answers we did and I don't have it in front of me. I don't know if it was interrogatory answers themselves but we indicated in fact that the statements that Mr. Sewell made at that time were not correct. THE COURT: Were not true; is that right? MS. WELLS: Were not true. THE COURT: I always like to use real English."

--Trial Tr. v. 1, p. 126, l. 22

"The incident involving security for President Bush was of an entirely different nature. It was offensive and deeply insulting to a loyal American who had spent her life in service to her government. It was unfathomable to the Court. Moreover, the government offered very little convincing evidence in explanation, other than to put Plaintiff to her proof and question whether it even happened. n33 - - - -Footnote- - - - 33. Charles P. Clapper, Jr. succeeded Plaintiff as Acting Regional Director, after she submitted her resignation. He testified that he was not aware that Plaintiff had been told that she could not attend the Independence Park ceremonies with the President and that he was satisfied that there had never been any direct orders to keep her out of the secure areas. However, he could not recall whether her picture had been circulated by law enforcement people, and indicated it could have been. He indicated that he talked with the law enforcement people and was satisfied that she would not pose a threat to the President. The Court found his testimony very vague and unspecific on crucial points. - - -End Footnote- - -"

"the Court concludes that Plaintiff has easily carried her burden of proof and established a prima facie case that she was denied her bonus in retaliation for filing a discrimination claim against the agency. The government offers no legitimate nondiscriminatory reason to explain the agency's actions other than a formalistic denial that, neither the PRB, nor the ERB considered gender, age, nor the fact that Plaintiff had filed a discrimination complaint. n29 Consequently, the Court concludes that, having considered all the evidence presented by the Plaintiff as well as having rejected the [*60] pro forma denials of the agency, the Plaintiff has proven, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the failure to award a bonus to Plaintiff for the 1990-1991 rating year was retaliatory. n30"

|

|

LEAD TRIAL AND APPELLATE COUNSEL

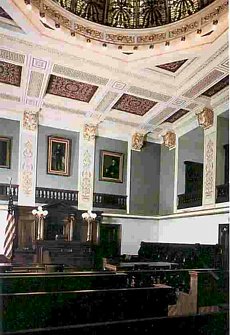

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

L. LORRAINE MINTZMYER, Plaintiff, v. BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary of the United States Department of Interior, Defendant.

Civil Action No. 93-0773 (GK)

1995 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 1182; 66 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1804

January 12, 1995, FILED COUNSEL: For L. LORRAINE MINTZMYER, plaintiff: Carl J. Hartmann, New York, NY; Paul J. Ruskin, Douglaston, NY; Mary C. McDonnell, MCDONNELL & MCDONNELL, Washington, DC. For JAMES H. RIDENOUR, in his capacity as the Director, National Park Service, and BRUCE BABBITT, in his capacity as the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Interior, defendants: Carlotta P. Wells, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, Civil Division, Washington, DC.

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW INTRODUCTION Plaintiff Lauretta Lorraine Mintzmyer brings this action for sex and age discrimination, constructive discharge, and retaliation against Defendant Bruce Babbit in his official capacity as Secretary of the Department of Interior. Plaintiff alleges that the Defendant discriminated against her on the basis of her sex and age when she was reassigned from the position of Regional Director of the Park Service's Rocky Mountain Region in Denver, Colorado to the position of Regional Director of the Park Service's Mid-Atlantic Region in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and was refused accommodations given to similarly situated, high-ranking males at the Department; that the Defendant retaliated against her by making an "improper" and false settlement offer in response to Plaintiff's equal employment opportunity claim, and by denying her a Senior Executive Service bonus and step increase; and that she was constructively discharged because her ability to manage her staff in the Mid-Atlantic Region was undermined by Defendant. Defendant contends that Plaintiff was not treated differently [*2] from similarly situated male employees; that there were legitimate management reasons for reassigning Plaintiff; that there was no retaliation against Plaintiff because of her equal employment opportunity claims; and that it took no actions to cause Plaintiff's alleged constructive discharge. The case was tried before the Court on November 1-7, 1994. The parties submitted, in addition to their pretrial briefs and memoranda, proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law. Upon consideration of the testimony of witnesses, the exhibits, and the entire record, the Court, pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 52, enters the following findings of fact and conclusions of law. FINDINGS OF FACT I. Parties Plaintiff Lauretta Lorraine Mintzmyer was an employee of the National Park Service ("Park Service"), United States Department of Interior ("Department"), from July 7, 1959 until April 4, 1992. During her career with the National Park Service, Plaintiff achieved extraordinary professional success. She rose from an entry level GS 4 Clerk/Typist to the position of Regional Director. She received the highest award - the Distinguished Service Award - offered in the Department during the course [*3] of her career. She was the first woman to be named superintendent of a major Park Service area. She was the first woman deputy director of a region. She was the first and only woman to serve as a Park Service Regional Director and headed more Regions (3) than any other person in the Park Service's history. She was also the most decorated female employee in the Park Service history. She was considered a highly competent, extremely effective, and valuable senior manager in the Park Service who was dedicated to the goals and mission of the Park Service to protect the treasures of our national park system. As Regional Director of the Rocky Mountain Region in Denver, Colorado, Plaintiff was the top management official for the Park Service within the Region and reported directly to the Director of the Park Service. Her responsibilities were broad and included oversight of the Region's park units and implementation of Park Service policies and procedures. She consulted frequently and regularly with the Director and other Park Service officials as well as others throughout the Department about major and controversial issues within the Region. She met, briefed and consulted with Congressional [*4] representatives as well as state and local governmental officials and citizens on a frequent basis. One of Plaintiff's duties as Regional Director for the Mid-Atlantic Region was to serve as co-chair of the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee ("GYCC"). The GYCC was established in the 1960's and was comprised of both Department of Interior Park Service employees and Department of Agriculture Forest Service employees. The mission of the GYCC was to develop a plan for the integrated management of National Parks in the area. The GYCC coordinated and drafted a document setting forth recommendations and goals relating to the greater Yellowstone area in 1990 which became known as the Vision Document. Congress mandated the preparation of this document. The purpose of the document was to develop coordination guidelines between the National Park Service and the Forest Service in order to facilitate protection of the Greater Yellowstone Area's ecosystem. Because early drafts of the Vision Document contained controversial recommendations, S. Scott Sewell, the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks at the Department, took control of the drafting process in October [*5] of 1990. n1 It is fair to say that Plaintiff and Sewell had very different, and incompatible, views about the Vision Document. On March 21, 1991, Sewell, a political appointee, demanded that Plaintiff, a career Civil Service employee, be reprimanded for allegedly lobbying members of Congress in February of 1991, while attending briefings on the Hill with legislative aides and committee staff members to discuss activities in their area of interest. Upon investigating the serious charges made by Sewell, the Director of the Park Service concluded that Plaintiff had not been lobbying, had instead been engaged in appropriate informational activities, and that there was no basis for such a reprimand. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - n1 All of Plaintiff's complaints about the manner in which efforts were made to redraft the Vision Document are being heard before the Merit Systems Protection Board under the Whistle-Blower Protection Act of 1989, Pub. L. No. 101-12, 103 Stat. 16 (1989) (codified at 5 U.S.C. Sec. 7701), and the Court makes no attempt to address those allegations. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -[*6] II. Organization of the Department of Interior The Park Service is a bureau within the Department of Interior, and is comprised of ten regions, each of which is managed by a Senior Executive Service ("SES") Regional Director. The Director of the Park Service is responsible for its overall operation and reports to the Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks. The Regional Directors communicate with the Director on an average of once a week on various issues of importance to each individual Region and Regional Director. The Performance Review Board ("PRB") reviews recommendations for bonuses submitted by the Director of the Park Service as well as those submitted by the Director of the Fish and Wildlife Service. The PRB is comprised of at least four and not more than seven SES members designated by the Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Those members must also be approved by the Executive Resources Board ("ERB"). The majority of the PRB members are career SES employees. The Chairman of the PRB in 1991 was Joseph Doddridge, Staff Assistant to the Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks. The other members of the PRB during the 1990-1991 rating year [*7] were Edward L. Davis, Associate Director for Budget and Administration; Jay Gerst, Assistant Secretary for Policy, Budget & Administration; and Sam Marler, Assistant Director for External Affairs. The ERB acts on behalf of the Secretary of the Department of Interior to develop and administer the Department's program for managing its executive resources and ensuring the selection of individuals capable of administering and managing the Department's many programs. The ERB is responsible for overseeing all personnel policies and procedures within the Department that affect SES employees. The ERB also influences the movement of SES employees and the distribution of SES positions within the Department. The ERB's functions include approving recommendations of individuals to fill SES positions; developing training opportunities for SES individuals; providing guidelines and standards for the SES Candidate Development Program; approving performance ratings, bonuses and level increases for SES employees; and authorizing reassignments of SES employees from one SES position to another or from an SES position to a non-SES position when the employee retains the same SES pay level in the non-SES [*8] position. All three of the members of the ERB, during the 1990-1991 rating year, were political appointees: R. Thomas Weimer, Chief of Staff to the Secretary; John Schrote, Assistant Secretary for the Office of Policy, Budget, and Administration; and Charles E. Kay, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Office of Policy, Budget and Administration. The Senior Executive Service is an elite management classification within the federal government. The SES, established under the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978, Pub. L. No. 96-330, 94 Stat. 1036-37 (1980) (codified at 5 U.S.C. Sec. 3131), rewards high-ranking government employees with a high pay scale and generous benefits. The SES also provides greater authority to agencies in managing their organizations including the ability to assign executives where they would be most effective in accomplishing the agency's mission. It is well understood and accepted throughout the Park Service that mobility is a key component of being part of the SES. Park Service employees often have to move long distances in order to ascend the career ladder. Career SES members may be reassigned to other SES positions for [*9] which they qualify in order to meet the needs of the Department and to promote the efficiency of the Park Service. Career SES members may also be detailed to another SES position. Details for more than 30 days must be submitted to the ERB for approval. Only in situations where the SES member is "acting" for another SES member is ERB approval not required for details beyond 30 days. III. SES Reassignments in the National Park Service When Manuel Lujan became Secretary of the Department of Interior in 1989, he expressed his concern that the Department's employees did not reflect the cultural and ethnic diversity of the nation as a whole. He directed the ERB to develop a diversified workforce that would be available to fill SES positions in the future and to devise ways in which to best utilize the existing SES resources of the Department. Acting upon the Secretary's direction, the ERB decided to implement a mobility policy in which individuals who had been in the same SES position for long periods of time would be moved from that position to another. The ERB determined that the goals and objectives of the Department would be better served if individuals with proven records of [*10] reliability, industry, and management ability could bring their experience and expertise to bear on new situations and problems. In late 1990, the ERB met with the Directors of the bureaus of the Department to discuss the proposed SES mobility policy. The ERB decided to implement the mobility policy on a bureau-by-bureau basis. The first units to reassign employees pursuant to this policy were the Bureau of Land Management and the Bureau of Reclamation. The ERB met with the Director of the Park Service, James M. Ridenour, on two to three occasions to discuss operation of the SES mobility policy within the Park Service. The ERB review of Park Service departmental records relating to SES employees revealed that Plaintiff who was Regional Director of the Rocky Mountain Region, Robert Baker who was Regional Director of the Southeast Region, and James Coleman who was Regional Director of the Mid-Atlantic Region, had each been in their respective positions for more than ten years. Director Ridenour concluded that the three SES employees who had been in their positions for more than ten years (Plaintiff, Baker, and Coleman) should be rotated and that Plaintiff would move to the Mid-Atlantic [*11] Region, Coleman would move to the Southeast Region, and Baker would move to the Rocky Mountain Region. The ERB approved Director Ridenour's plan to effectuate this three-way rotation. In May 1991, a Regional Directors' meeting was held in St. Louis, Missouri in which Director Ridenour and the Deputy Director of the Park Service, Herbert S. Cables, informed Plaintiff, Baker and Coleman about the proposed three-way reassignment. Upon meeting with Ridenour, Plaintiff, Baker and Coleman individually and separately strongly objected to the reassignments and gave personal reasons for remaining in their respective positions and Regions. Plaintiff was unwilling to be reassigned because she was providing financial and personal support to her husband (from whom she had lived apart for 8 years) who lived in Nebraska and was in extremely poor health; in addition, she did not wish to move because a close male friend resided in Denver. Baker was unwilling to be reassigned because his children and grandchildren resided in the Atlanta area, he had property there and he had begun several projects in the Southeast Region that he wanted to complete. Coleman was unwilling to be reassigned because his [*12] wife recently had obtained a job for the first time in 20 years and his children resided in the Philadelphia area. All three expressed great professional and personal satisfaction with their existing assignments. On May 15, 1991, Plaintiff, in response to her private conversation with the Director concerning the proposed reassignment, sent a memorandum informing him that she would possibly be retiring in 1993, but no later than January 1994. n2 On May 16, 1991, Director Ridenour, concerned that a relatively large number of senior managers would soon be retiring, issued a memorandum directing all SES employees to inform the Director of their views regarding reassignment and any retirement plans that would affect their careers as Park Service employees. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - n2 Plaintiff also indicated, in an attempt to avoid imposing her moving costs on the Department, that she would commit to retire on January 1, 1993, when she was still in Denver, or be agreeable to a transfer at that time. n3 In May of 1991, 17 out of 21 SES personnel in the Park Service were eligible for retirement. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -[*13] After considering personal concerns given by the Regional Directors facing the three-way reassignment, Director Ridenour decided that the benefits to the Park Service of the three-way reassignment outweighed such personal concerns and that he would proceed with his original plan. On June 25, 1991, he sent a memorandum containing identical language to the three Regional Directors informing them that he was directing the three-way reassignment, that they would retain their SES status and level, that they would be removed from federal service if the reassignment was not accepted, and that the reassignment would be effective 60 days from receipt of the memorandum. Thereafter, Plaintiff was reassigned to the position of Regional Director for the Mid-Atlantic Region of the National Park Service in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Robert Baker was reassigned to the position of Regional Director for the Rocky Mountain Region in Denver, Colorado; and James Coleman was reassigned to the position of Regional Director for the Southeast Region in Atlanta, Georgia. At the time of the reassignment at issue in this case, Plaintiff was 56 years old and had been Regional Director of the Rocky Mountain [*14] Region for 11 years; James W. Coleman was 55 years old and had been Regional Director of the Mid-Atlantic Region for 11 years; and Robert M. Baker was 53 years old and had been Regional Director of the Southeast Region for 10 years. After the three-way reassignment was officially announced in the June 25, 1991 memorandum, Plaintiff and the Director, during a meeting at Mount Rushmore in early July 1991, discussed the possibility of her taking the position of Associate Director for Strategic Planning which would require her resignation from the Senior Executive Service. In July 1991, there was only one SES position in Denver, and that was Regional Director. On July 15, 1991, in response to the discussions between Plaintiff and Director Ridenour at Mount Rushmore, Ridenour, in an effort to accommodate Plaintiff's desire to remain in Denver, Colorado, sent a memorandum to Plaintiff asking that she consider the position of Associate Director for Strategic Planning, to be located in Denver. Director Ridenour felt that Plaintiff was an outstanding employee and that her talents in management would further the Park Service's efforts to develop a strategic planning capability. Moreover, since [*15] Plaintiff had told him that she was planning to retire in two or three years, he felt that if she took the Strategic Planning position, she could stay in Denver as she wished, earn her same SES pay, retire at that level, and perform useful and creative work for the Park Service before retiring. At Ridenour's request, Plaintiff drafted a position description and budget for the Strategic Planning office, but indicated that she would only take the position if the Director was committed to the task of moving the Service forward and if the position was at the same SES level (ES-4) and pay that she was receiving. Director Ridenour approached the ERB about establishing the Associate Director for Strategic Planning position at the SES level. Ridenour was advised that, given the limited number of authorized SES slots, the Department had no SES slots available for the Strategic Planning position and that there could be no such SES allocation in the immediate future. Director Ridenour then offered Plaintiff the Associate Director for Strategic Planning position at the GM-15 level with retained pay at her existing SES level. Director Ridenour advised Plaintiff to contact the ERB directly to discuss [*16] the possibility of allocating an SES slot to the Strategic Planning position. In a July 24, 1991 memorandum to the Director, Plaintiff indicated that she had spoken with the Director of Personnel for the Department who informed her that it was unlikely that an SES slot would become available for the Strategic Planning position. Plaintiff was opposed to accepting a non-SES position because she feared that her resignation from the SES would make her vulnerable to personnel actions, including RIFs, based on her opposition to the redrafting of the Vision Document. Unwilling to accept a downgraded position which would result in the loss of potential SES bonuses and the ability to accrue an unlimited amount of annual leave, Plaintiff ultimately rejected the Associate Director for Strategic Planning position in mid-July 1991. On July 24, 1991, Plaintiff filed an informal administrative complaint of sex and age discrimination, naming Herbert Cables as the discriminating officer. In light of the fact that Baker and Coleman had already accepted their reassignments and Plaintiff had rejected the Associate Director for Strategic Planning position, Director Ridenour on July 25, 1991, requested [*17] formal authorization to reassign Plaintiff to the Mid-Atlantic Region. n4 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - n4 While Plaintiff understandably makes much of the sequence of these two events, there is nothing in the record to show that Director Ridenour knew, on July 25, 1991, that Plaintiff had filed her informal administrative complaint the previous day. He specifically denied having any knowledge of when she filed her complaint. Moreover, as shown above, the reassignment had been announced in May, 1991. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - In August 1991, Deputy Director Cables, knowing that he was named as the alleged discriminating officer in Plaintiff's EEO complaint, n5 had lunch with Heather A. Huyck, who served on the Majority staff of the House Subcommittee on Parks and Insular Affairs. Cables asked Huyck, as a personal friend of Plaintiff, to contact her and recommend that she talk to Director Ridenour about obtaining an SES position. Cables also made it clear that plaintiff's counsel should not be involved in the matter. Cables stated that if Plaintiff would accept the Strategic [*18] Planning position at the GM-15 level, an SES allocation could be obtained at a later time. Huyck spoke to Plaintiff who then contacted the Director. To her humiliation and embarrassment, however, Plaintiff discovered that the Director had no knowledge of what Cables had discussed and saw no possibility that the GM-15 Strategic Planning position could, with any certainty, be later allocated to an SES status. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - n5 The Court does not credit Cables' denial of this fact. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - On September 5, 1991, Plaintiff filed a formal complaint of sex and age discrimination, and retaliation with the Department of Interior. IV. Park Service Officials to Whom Accommodations Were Allegedly Made A. Denis P. Galvin From 1985 to 1989, Denis P. Galvin, a member of the SES, served as the Deputy Director of the Park Service. While serving as Deputy Director, Galvin had disagreements with and was being subjected to criticism of his job performance from a politically appointed Department Assistant Secretary, Becky Norton Dunlap. It is the long-standing [*19] practice at the Department that when a new administration assumes power, a new Director of the Park Service is appointed who in turn selects his own new Deputy Director. On April 7, 1989, Galvin was informed that he would be replaced by Cables, then Regional Director of the North-Atlantic Region of the Park Service, who would become the Deputy Director under the Bush Administration. However, Cables could not move into the position of Deputy Director until another position was found for Galvin within the Park Service. Although he continued to officially hold the position of Deputy Director, Galvin was moved out of the Washington, D.C. offices for more than 30 days. Although there was testimony and some exhibits to demonstrate that Galvin was sent to the Harpers Ferry Center in West Virginia to conduct a management survey, the record is far from clear as to his precise status or duties. Galvin admitted that all supporting documents concerning his move were prepared after the fact. Galvin expressed a strong desire to remain in the Washington, D.C. area and not be reassigned elsewhere because he did not wish to cause further disruption in the lives of his wife and children who were in [*20] Washington, D.C. Galvin informed Director Ridenour that he was willing to step down from the SES and accept a GM- or GS-15 position in order to remain in Washington, D.C. During the spring of 1991, there were a number of SES jobs open in Washington, D.C. which Galvin applied for and did not obtain. On June 13, 1989, Galvin finally received a directed reassignment to the position of Regional Director for the North-Atlantic Region in Boston, Massachusetts, with a detail to the Washington, D.C. office for a period not to exceed a year to complete a number of projects. On June 27, 1989, Galvin, acting in accord with his previously stated views, refused to accept the directed reassignment to the North-Atlantic Region and repeated his willingness to accept a non-SES position in order to remain in Washington, D.C. with his family. After receiving permission from Cables, Galvin approached Gerald Duane Patten, Associate Director for Planning and Development, on June 20, 1989, to ascertain Patten's willingness to be reassigned to the North-Atlantic Region. PAGE 31 1995 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 1182, *; 66 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1804 Patten expressed his willingness and in July 1989, a three-way reassignment was executed in which Galvin did manage to obtain all that he [*21] wanted: he remained in Washington, D.C., was reassigned to the position of Associate Director for Planning and Development, and retained his SES status. Patten was reassigned to the position of Regional Director for the North Atlantic Region, and Cables was officially reassigned to the position of Deputy Director which he had been holding, unofficially, since April, 1989. B. Gerald Duane Patten As noted above, Gerald Duane Patten, a member of the SES, was reassigned to the North Atlantic Region in July, 1989. Thereafter, his fiancee, who had initially taken a job outside of the National Park Service, was able to negotiate with the Director of the Harpers Ferry Center of the Park Service and obtain a GS-12 position in the Salem, Massachusetts office of the Harpers Ferry Center. After her job in Massachusetts ended, she obtained a position with the Denver Service Center of the Park Service, and moved to Denver in May, 1991. Subsequently, Patten informed Director Ridenour that he was interested in reassignment to the western part of the country. In October of 1991, Patten was offered the Associate Director for Strategic Planning position in Denver, Colorado. In January of 1992, Patten [*22] stepped down from his SES position as Regional Director in Boston and accepted the Associate Director for Strategic Planning position at a GM-15 level with retention of his SES salary. C. Quincy Boyd Evison From September, 1985 until June, 1991, Quincy Boyd Evison, a member of the SES, was the Regional Director of the Alaska Region of the Park Service. In early 1991, Evison spoke with Director Ridenour about a reassignment out of Alaska because of difficulties in dealing with the local congressional delegation and personal concerns relating to his mother-in-law's need for specialized medical care. Evison explored several options, including the position of Associate Director for Operations in Washington, D.C. He eventually decided to accept the non-SES position of Deputy Director for the Rocky Mountain Region, at a GM-15 level with retention of his SES salary. D. Herbert S. Cables Herbert S. Cables, a member of the SES, was notified that he would be replaced as Deputy Director, as a result of a Department of Interior investigation involving contracts approved by him when he was Regional Director of the North-Atlantic Region. Cables then expressed his desire to move to the New York [*23] City area because he had aging relatives and a house located there. In August, 1993, with no SES position available in the New York City area, Cables, upon his request, was reassigned, through an Intergovernmental Personnel Assignment, to the City University of New York and retained his SES status and pay. The Intergovernmental Personnel Assignment was created as a result of Cables' own efforts to find an SES position in the New York City area. VI. Plaintiff's Resignation Plaintiff's reassignment to the Mid-Atlantic Region was effective on October 6, 1991. Although initially distressed about the reassignment, Plaintiff made up her mind to go to Philadelphia and do as high quality a professional job as she always had. During her tenure as Regional Director of the Mid-Atlantic Region, from October 6, 1991, until April 4, 1992, Plaintiff undertook a strenuous schedule to visit all park units and the offices of each member of Congress for the Region by April, 1992. When Plaintiff arrived as Regional Director of the Mid-Atlantic Region three difficult personnel situations faced her, involving Fontaine Black, Sandra Rosencrans and Bill Wade, that had not been resolved by the former [*24] Regional Director, James Coleman. Fontaine Black was the Regional Equal Employment Opportunity Officer for the Mid-Atlantic Region. With the permission and approval of Coleman while he was Regional Director of the Mid-Atlantic Region and the knowledge and acquiescence of high-level management officials in Washington, D.C., Black worked on projects that had an impact beyond her own Region. For example, she recruited minority students into the Park Service for the Mid-Atlantic Region and other regions. She also worked on the Historically Black Colleges and Universities program and the interpretation of slavery initiative program. In November of 1980, Black filed an EEO complaint alleging that failure to reclassify her position as a GM-13 was a result of race discrimination. She ultimately prevailed on this charge. In the summer of 1991, Black requested that her Service-wide activities be recognized and that her position be upgraded from a GM-13 to a GM-14 level. In September 1991, Coleman as Regional Director requested approval to reclassify Black's position and upgrade her GM level. No such approval was given. Upon arriving as Regional Director in Philadelphia, Plaintiff immediately [*25] turned her attention to the issue of reclassification of Black's position. On October 4, 1991, Plaintiff received a memorandum from Associate Director for Budget and Administration Edward Davis notifying the Mid-Atlantic Region that classification of the GM-14 level was in the Region's delegation of authority, but cautioning against using as a basis for the upgrade any duties and responsibilities assigned to the Washington Office. In a memorandum of December 16, 1991, Cables advised Plaintiff that, contrary to Davis' advice, he thought that Regional Directors, carrying out the wishes of the Director, could assign duties of national scope to members of their staffs for development and implementation. Because of the conflicting interpretations of her authority to reclassify Black's position, Plaintiff requested specific authorization from Cables to upgrade Black's position. Once again, because of the Park Service's failure to reclassify her position properly (this time to a GM-14) Black filed an EEO complaint, on January 8, 1992, naming Plaintiff as the alleged discriminating officer. n6 In a January 15, 1992 memorandum Cables responded that it was the Region's responsibility, not his, [*26] to revise the position description for a Regional employee. He also cautioned that authority to conduct any program on a Servicewide basis, as opposed to activities that encompassed more than one Region, but were not Servicewide, must be delegated by the Washington, D.C. office. The reclassification of Black's position was not settled before Plaintiff resigned as Regional Director of the Mid-Atlantic Region, although Ms. Black did ultimately successfully settle her EEO claims and received a GM-14. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - n6 Ms. Black also filed discrimination complaints on February 20, 1992, and April 17, 1992. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Sandra Rosencrans was the Associate Regional Director for Administration. As a result of the death of her husband and subsequent health problems, Rosencrans was unable to perform her job functions adequately. Because Rosencrans was no longer effective in her job, Plaintiff proposed directing her reassignment with the understanding that Rosencrans would refuse the reassignment, and, thereafter be eligible for a discontinued service [*27] retirement. Rosencrans did finally retire while Plaintiff was still Regional Director of the Mid-Atlantic Region. Bill Wade was the Superintendent of Shenandoah National Park. Wade was reprimanded by Mr. Coleman prior to Plaintiff becoming Regional Director for the Mid-Atlantic Region. Plaintiff thought that it was Director Ridenour's desire that she reprimand Wade in connection with statements he had made to the press regarding air quality issues in Shenandoah National Park. However, she agreed with Wade's position, and never reprimanded him. There were no repercussions. On April 3, 1992, President George Bush was scheduled to visit Independence Park in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At this time Plaintiff was returning from congressional appropriations hearings in Washington, D.C. Plaintiff was informed by Park Service employees that she was not to be allowed within a set perimeter of the President, and that to ensure that this security measure was carried out, her picture was circulated at the briefing for law enforcement officials. Plaintiff was shocked and profoundly offended to learn that she was viewed as a security risk to the President of the United States and would be barred [*28] from attending an important public ceremony on Park Service property within her jurisdiction. Concluding that her position with the Park Service had become untenable, on March 27, 1992, Plaintiff faxed a memorandum to Director Ridenour retiring from her position as Regional Director of the Mid-Atlantic Region. VII. Park Service Bonus and Step Increase The Department's evaluation and bonus system is designed "to provide recognition and reward for senior executives who demonstrate high levels of achievement." Department of Interior Departmental Manual at Chapter 920, Sec. 6.1 The rating period runs from July 1 through June 30 of each year. Recommendations regarding an SES employee's performance rating and bonus are made by the Director. Recommendations are then reviewed by the PRB. The PRB's recommendations are forwarded to the Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks who determines the final rating. The Assistant Secretary reviews the recommendations of the PRB and forwards his recommendations to the ERB. The ERB approves all SES bonuses, awards and level increases for the entire Department. On August 8, 1991, Director Ridenour recommended Plaintiff for a bonus of $ 5,025 [*29] and an SES level 4 performance rating n7 to the PRB. Plaintiff had received numerous bonuses and grade increases when eligible in the past. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - n7 A level 4 rating which falls under a category labeled "Exceeds Fully Successful," means that the employee's performance as manager exceeded performance expectations. See Individual Senior Executive Performance Appraisal Career Appointee Career Appointee, Lauretta Lorraine Mintzmyer, Defendants' Exhibit 11. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - On August 14, 1991, the Fish, Wildlife and Parks PRB convened to review the recommendations from Director Ridenour for the 1990-1991 rating year. Although accepting Director Ridenour's recommendation that Plaintiff receive a level 4 performance rating, the PRB refused to accept his recommendation of a bonus for Plaintiff. The Assistant Secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks did not alter the PRB's recommendation with respect to Plaintiff's performance rating and bonus. The ERB then adopted the Assistant Secretary's position regarding Plaintiff on November 22, 1991, and [*30] she did not receive the bonus originally recommended by Director Ridenour. Plaintiff was the only female Regional Director and the only Regional Director denied a bonus. There were only two female SES Park Service employees. One, the Plaintiff, was recommended for a bonus and was denied it. The other, a Ms. Gilliard-Payne, was recommended for a step increase and was denied it. Both females had filed an EEO complaint against the Department. Both women ultimately left the Agency. CONCLUSIONS OF LAW Plaintiff is bringing claims under both Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2000e, n8 and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 ("ADEA"), 29 U.S.C. Sec. 621 et seq. n9 Preliminarily, the Court will set forth the applicable general principles, by now well established under existing Supreme Court case law, pertaining to each party's shifting burdens of proof, production, and persuasion. Next, the Court will apply those principles to the specific claims asserted by the Plaintiff. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - n8 Title VII provides that:

42 U.S.C. Sec. 2000e-2(a)(1) and (2). [*31] n9 The ADEA provides that: